more about thimbles

Victorian Pictorial (‘castle’), commemorative and souvenir thimbles 1

Magdalena and William Isbister.

Fig 1

Alexandrina Victoria was born in May 1819. She was the niece of William lV and inherited the throne at eighteen years of age (Fig 1). In 1840 she married her first cousin Prince Albert of Saxe-Coburg and Gotha. She died in 1901 and was the longest ruling British monarch. Her subjects were known as the ‘Victorians’ and during her reign they built palaces, bridges, and tunnels, they travelled widely and attended expositions in great numbers. Victorian thimble makers were quite prolific and unquestionably made more ‘pictorial’ thimbles than any other thimble makers either before Victoria came to the throne or after her death. Many thimbles commemorated the Queens reign but many other Victorian activities were illustrated on these thimbles (sometimes called ‘commemorative’, ‘castle’, or ‘souvenir’ thimbles) too. In this paper examples of these ‘pictorial’ thimbles will be described.

The Reign

Very few of the thimbles commemorating the Queen’s reign seem to be marked but the makers of a few of the thimbles are known.

General

Several thimbles were made depicting either the Queen or simply bearing her name (Fig 2). It is not known whether they commemorated any specific event during her reign.

Fig 2

The left thimble is a simple thimble with a decorated rim and ‘Victoria’ on a ribbed border. The other thimble is taller and was probably made to commemorate the accession or coronation of the Queen. It has a border decorated with a bust of the young Queen in a leafy wreath and ‘Victoria’ written between rose garlands.

Ascending the Throne/Coronation

Fig 3

This thimble (Fig 3) has a plain border with an engraved crown and ‘Queen Victoria born May 24 1819, Ascended the throne June 20 1837, Crowned June 28 1838’.

Fig 4 Fig 5

The left thimble (Fig 4) has a plain ribbed border with ‘Victoria’, a crown, and ‘crowned’ and then below >>>>>1st<<<<< ‘June. 28. 1838’. The right thimble (Fig 5) also has a ribbed border decorated with a crown interspersed with shamrock, thistle and roses and ‘Victoria 1st Crowned June 28th 1838’.

Wedding

Fig 6 Fig 7 Fig 8

Busts of both Albert and Victoria are to be found on most of the thimbles made to commemorate the Royal Wedding. The border of the left thimble (Fig 6) is decorated with the busts and roses, daffodils, shamrock and thistles. The middle thimble (Fig 7) is decorated with rose, thistle and clover and a medallion containing the busts of Albert and Victoria, the words ‘Victoria and Albert’ are in the medallion above the busts. The right thimble (Fig 8) has small busts and ‘Albert born Aug 26. 1819’ on one side and ‘Victoria born May 24. 1819’ on the other side. ‘ Married at St James’s Palace Feb 10, 1840’ is stamped on the rim.

Fig 9

This heavily dimpled, cast, pewter thimble (Fig 9) has ‘Victoria-Albert 1840’ printed around the border and a decorated rim. The original thimble was made to commemorate the wedding of Victoria and Albert by an unknown maker, and this copy was made by Westair Museum Reproductions, Birmingham in the 1990s.

Crowning of the Prince of Wales

Edward VII was the second child of Queen Victoria and Prince Albert and within about a month of his birth he was pronounced ‘Prince of Wales’. Several thimbles were made to commemorate this event.

Fig 10 Fig 11

The border of the thimble on the left (Fig 10) has a figure on a throne on one side of which ‘Prince of Wales our future hope’ is written and on the other side of which ‘Heir to British throne born Nov 9 1841’ is written. ‘Christened at Windsor Jany 25 1842’ is printed on the rim. The right thimble’s (Fig 11) border is decorated with the Prince of Wales feathers and ‘Ich Dien’.

Golden Jubilee

In 1887 Victoria celebrated her Golden Jubilee and at least one thimble was made to commemorate this occasion.

Fig 12

The thimble (Fig 12) is made of nickel silver and has a plain flat border and rim with ‘Victoria’, a crown, and ‘Jubilee’. It was made by Charles Iles and Company.

Diamond Jubilee

Fig 13 Fig 14

The left thimble (Fig 13) has an applied border with ‘Commemoration of the diam | 1837-1897 | ond jubilee of Queen Victoria’ above a thistle, VRI, a shamrock, a crown, a rose, and a bust of the Queen. It is marked 0, D & F, and Rd. 295282 (Hamilton & Inches [goldsmiths] Victoria Jubilee thimble). It was made by Deakin & Francis of London. The right thimble (Fig 14) is a cast pewter copy and has a single hole in the rim to signify that it is a copy. It was made by Stephen Frost, Warwick Models, England in the late 90s.

Fig 15 Fig 16

The left thimble (Fig 15) has a ribbed border decorated with an applied chain and 3 shields containing ‘37’, ‘VR’, ‘97’. It was made by Henry Fowler of Birmingham. The right thimble (Fig 16) is very plain but has ‘JUBILEE + 1887’ around the rim.

Engineering

One of the important engineering developments during the Victorian era related to communication. Coaches, canals, steam ships and the railways allowed goods, raw materials and people to be moved about rapidly, thus facilitating trade and industry. Trains became such an important factor in ordering society that "railway time" became the standard for setting clocks throughout Britain. Steam ships made international travel and advanced trade possible. The introduction of the first postage stamp, the ‘Penny Black’, meant that letters cost a penny irrespective of distances sent.

Fig 17

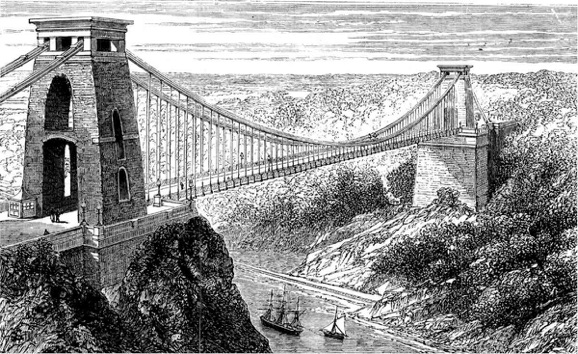

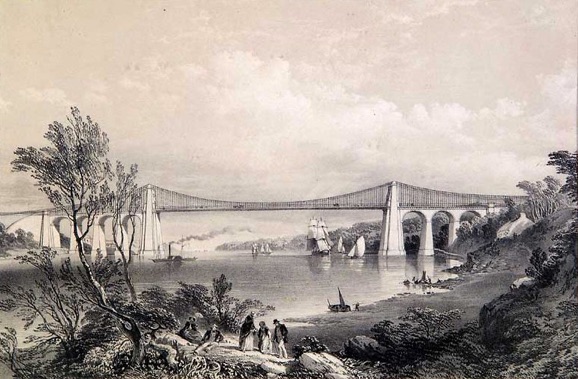

The Clifton Suspension Bridge (Fig 17) which spans the Avon Gorge and links Clifton in Bristol to Leigh Woods in North Somerset was designed by Isambard Kingdom Brunel. The idea of building a bridge across the Avon Gorge originated in 1753. An attempt to build Brunel's design in 1831 was stopped by riots in Bristol and work was not started again until 1836. The bridge was finally completed in 1864. The ironwork for the bridge was cast at the Hazledine Foundry in Coleham, Shrewsbury. The bridge was started in 1819 and opened on 30th January 1826. Thomas Telford had rejected the original designs claiming that no suspension bridge could exceed the 577 feet span of his own Menai Suspension Bridge (Fig 18). This bridge was built over the Menai Straits between Anglesey and the Welsh mainland by Thomas Telford.

Fig 18

A silver thimble depicting the Menai Suspension Bridge was made in the 1840s. It was made by George Unite of Birmingham in 1826. The bridge differs from the Clifton Bridge in that there are four arches on the Anglesey (left) side of the main span and three arches on the Mainland (right) side in the Menai Bridge whereas the Clifton Bridge has no arches at all.

Fig 19 Fig 20

George Unite of Birmingham, made the Menai Bridge thimble (Fig 19) which is only marked ‘GU’. A silver thimble (Fig 20) with three arches on either side of the main span is clearly a representation of neither bridge but it is marked ‘Clifton Suspension Bridge 1864’ around the rim and must have commemorated the opening of the bridge. The maker of this thimble is unknown.

Another great engineering feat of the Victorian age was the sewage system in London. It was designed by Joseph Bazalgette in 1858. The Thames Embankment, also designed by Bazalgette housed the sewers, water pipes and parts of the London Underground District and Circle lines. During the same time London's water supply network was expanded and improved, and a gas network for lighting and heating was introduced in the 1880s.

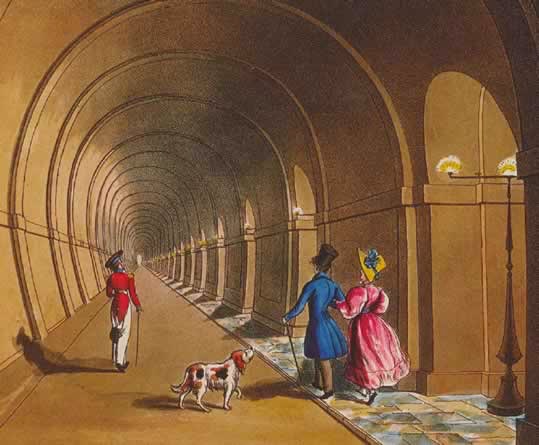

Other major engineering achievements during Queen Victoria’s reign include the Crystal Palace in 1851 (see below), Isambard Kingdom Brunel’s Saltash Railway Bridge (1859) and SS Great Eastern (1858), the Tower subway under the Thames (1869), Hammersmith Bridge (1824), the Tower Bridge (1886), Reid’s climate control systems (1835), the Pontcysyllte Aqueduct in North Wales (1805), the Britannia Tubular Railway Bridge, a companion to the Menai Suspension Bridge, (1850), and the Thames Tunnel (1843). With the exception of the Crystal Palace and the Thames Tunnel none of these events were commemorated on thimbles.

The Thames Tunnel was an underwater tunnel, built beneath the River Thames and connected Rotherhithe and Wapping. It was 35 feet wide, 20 feet high and 1,300 feet long. It passed, at a depth of 75 feet (measured at high tide), below the river's surface. It was built between 1825 and 1843 and was the first tunnel known to have been constructed successfully beneath a navigable river using Thomas Cochrane and Marc Isambard Brunel's newly invented tunneling shield technology. It was originally planned as a pedestrian tunnel and carriageway so that Victorians could cross the Thames easily and quickly (Fig 21). Plans to open the tunnel as a carriageway however failed due to cost and financially the tunnel was not a success.

Fig 21

It was purchased in 1865 by the East London Railway Company in order to provide a rail link for goods and passengers between Wapping and the South London Line. The tunnel's generous headroom, resulting from the need to accommodate horse-drawn carriages, additionally allowed sufficient space for trains.

Fig 22

The first train ran through the tunnel in December 1869. In 1884, the tunnel's disused pedestrian entrance shafts in Wapping (Fig 22) and Rotherhithe were converted into stations. The East London Railway was later absorbed into the London Underground, where it became the East London Line. It continued to be used for goods services as late as 1962. In 1995 it was closed for long-term maintenance and was finally reopened again for main line passenger trains in 2010.

A brass thimble (Fig 23) was made to commemorate the opening of the tunnel in 1843. In addition to a bust of Queen Victoria, ‘Visited the’ followed by a depiction of the tunnel and the date which seems to be ‘July 26 1843’ is printed around the border.

Fig 23

Buildings

Queen Victoria did not like the Brighton Pavilion as a summer home and rural retreat but, as she had spent enjoyable holidays on the Isle of Wight as a young girl, she and her husband decided to buy Osborne House on the Isle of Wight in 1845. They liked the setting of the house but it was too small for their needs so Prince Albert designed a new house in the style of an Italian Renaissance palazzo and the earlier smaller house on the site was demolished. The builder was Thomas Cubitt, the London architect.

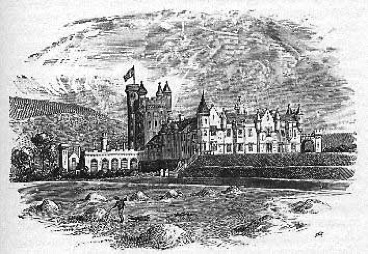

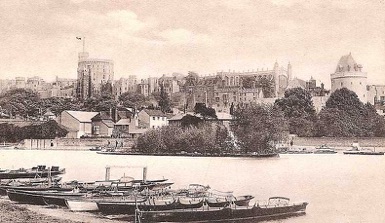

Osborne House (Fig 24), built by the Victorians, together with two other Royal residences, built before Queen Victoria ascended the throne, Balmoral (Fig 25) (bought by Queen Victoria in 1852) and Windsor (Fig 26), are all commemorated on thimbles made during the latter period of the Queen’s reign. They differ from earlier thimbles in that they were deep drawn and have flat turnover rims which were stamped with the name of the dwelling. The ‘Osborne House Isle of Wight’ and ‘Windsor Castle’ thimbles were made by Samuel Foskett of London in 1901 and 1894 respectively. The other thimble is unmarked.

Fig 24

Fig 25

Fig 25

Pursuits (travel and sightseeing)

Victorians loved to travel for leisure and used all methods of mechanised transportation available to them at the time - bicycle, train and boat.

Bicycle

The bicycle was particularly attractive to women because it gave them greater freedom to travel around. Susan B. Anthony, a member of the American women’s suffrage movement, said that it had “done more to emancipate women than anything else in the world.” although clearly it was not all ‘plain sailing’ (biking) as this advertisement (Fig 26) of the day indicates.

Fig 26

This, the simplest form of mechanized transport, is illustrated in the so-called ‘Blackberry’ series where some of the Blackberry thimbles depicted a bicycle on the border.

Fig 27

Fig 28

There were several bicycle designs (1) - with and without a cross bar (Fig 27), with and without a chain mechanism (Fig 27) and with solid tyres (Fig 27) or tyres with holes (Fig 28) and these differences probably reflect the inclination of the particular engraver responsible for engraving the thimble. Opposite the bicycle was an engraved bird (Fig 27). The thimbles were made by James Fenton, Birmingham, in 1896 and 1901 (Rd 280564).

References

1. Spicer N. James Fenton Silversmith and Thimble Maker etc. 1994. pp. 27.

Holmes: ‘Commemorative Thimbles' pp. 173, 'Souvenir Thimbles' pp. 182.

Researched and published in 2002/11

Copyright@2011. All Rights Reserved

Magdalena and William Isbister, Moosbach, Germany

Navigation